Hidden in Plain Sight: The Return of the Q-Ship in Modern Naval Warfare

The Concept:

Imagine a warship that doesn’t look like a warship. It sits in a busy shipping lane, indistinguishable from the thousands of merchant vessels hauling goods across the globe. It carries no visible cannons, no grey hull, and flies a commercial ensign. Yet, beneath the rusted exterior of a tramp steamer or the mundane stack of ISO containers lies a capability that rivals a frigate.

History is repeating itself. In the First World War, the Royal Navy deployed “Q-ships” heavily armed merchant vessels designed to lure German U-boats to the surface. Today, as naval warfare enters the “Grey Zone,” the concept is returning with a high-tech twist. Nations are looking for plausible deniability, cost-effective force multipliers, and the element of surprise.

Here is how the modern Q-ship is reshaping the seas, from the straits of Gibraltar to the South China Sea.

The Enforcer: Up-Armoured Tugs

Naval dominance isn’t always about over-the-horizon missiles; sometimes, it’s a shoving match. In contested waters like the South China Sea or the Gibraltar Strait, “Grey Zone” warfare often involves non-kinetic confrontation blocking manoeuvres, ramming, and physical intimidation.

The Gap: “Grey Zone” Physical Confrontation Modern warships are built for long-range destruction, not close-quarters brawling. Using a £1 billion destroyer to physically block or “shoulder” a hostile fishing boat is a massive financial risk and a political escalation trap. Navies lack a rugged, expendable asset designed for the rough-and-tumble of asserting sovereignty in contested waters like the Gibraltar Straits or the South China Sea.

The Concept: A vessel based on a heavy-duty harbour tug or icebreaker hull. These ships are defined by massive torque, reinforced steel bows, and powerful water cannons.

How it works: The vessel retains the civilian tug’s towing capability but is fitted with internal armour plating around the bridge and engine room. The hull is reinforced specifically for “shouldering” the naval tactic of physically ramming or pushing an opposing vessel to force it to change course.

The “Q” Element: It looks like a standard piece of port infrastructure drab, industrial, and non-threatening. However, it is effectively a “street fighter.” It can operate aggressively against maritime militias or hostile state actors without technically acting as a warship, keeping the conflict below the threshold of open war.

Royal Navy Use: Deployed to Gibraltar or the Falklands, these “Enforcers” could physically push Spanish incursions or illegal fishing fleets out of territorial waters without risking the paintwork on a Type 45 Destroyer.

Standard grey-hull warships are expensive and politically sensitive assets. Deploying a Destroyer to bump hulls with a fishing militia vessel risks escalation and costly repairs. An up-armoured tug, however, is built for the brawl. With reinforced hulls, powerful engines, and water cannons, these vessels can physically push hostile actors out of territorial waters. They offer a rugged, low-cost solution for asserting sovereignty without firing a shot, allowing navies to hold the line in the rough-and-tumble world of sub-threshold warfare.

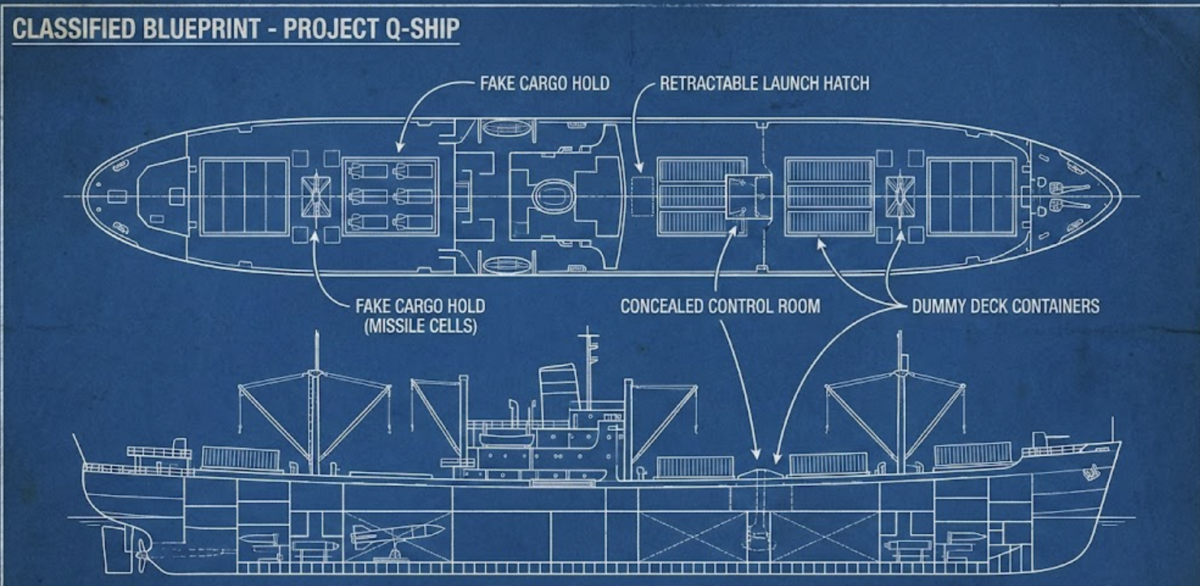

The Missile Merchant: Death by ISO Container

Modern Q-ships can turn a standard container ship into a strike platform by mixing “Missile Containers” with regular freight. These adapted ISO containers house long-range land-attack or anti-ship missiles, indistinguishable from the boxes carrying electronics or furniture next to them.

The Gap: Distributed Lethality Building enough warships to cover every shipping lane is impossible. Navies need a way to project power in thousands of locations simultaneously without building thousands of new hulls.

The Concept: The integration of modular weapon systems, such as the Russian “Club-K” or emerging Western equivalents, into standard 40ft ISO shipping containers.

How it works: A standard container ship carries thousands of boxes. A “Missile Merchant” replaces just four or five of these with weaponised units. These containers house a self-contained launch system, radar, and command module. When activated, the roof of the container lifts, and missiles (anti-ship or land-attack cruise missiles) are erected and fired directly from the deck.

The “Q” Element: This is the ultimate camouflage. The vessel is indistinguishable from a furniture carrier on radar or satellite imagery. The enemy cannot identify the threat until the moment of launch, forcing them to treat every commercial radar contact with caution, diluting their focus.

Royal Navy Use: A Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) supply ship could carry a “defensive stack” of these containers, allowing it to protect itself or contribute to a strike mission without needing a frigate escort.

This concept forces an adversary to treat every commercial radar contact with suspicion. A single merchant vessel could park off a coastline and unleash a barrage of precision strikes before the enemy even identifies a threat. It provides a massive asymmetrical advantage, turning logistics networks into potential kill chains.

The Silent Listener: Intelligence in the Stack

Information is as lethal as gunpowder. Intelligence agencies can now embed high-grade surveillance suites directly into the supply chain.

By fitting merchant ships with SIGINT (Signals Intelligence), COMINT (Communications Intelligence), and ELINT (Electronic Intelligence) equipment hidden inside modified containers, navies can deploy sensors virtually anywhere. These “Spy Ships” don’t need to loiter suspiciously; they simply sail their commercial route, vacuuming up radar frequencies, radio chatter, and electronic emissions from coastal defences or rival fleets.

The Gap: Persistent Coastal Surveillance Gathering intelligence on enemy coastal defences usually requires obvious “spy ships” (AGIs) that are easily tracked and blocked. Navies need a way to map enemy radar and communications without alerting the target.

The Concept: A merchant vessel fitted with “smart containers” hidden within the main cargo stack. These containers house SIGINT (Signals Intelligence) arrays, electronic warfare suites, or loitering drone swarms.

How it works:

- Surveillance: The ship sails a standard commercial route into a port of interest. While docked or transiting, the hidden equipment passively vacuums up radio frequencies, radar emissions, and mobile phone traffic.

- Drone Strike: In a combat scenario, specific containers open to launch a swarm of suicide drones (loitering munitions) to overwhelm air defences or attack port infrastructure.

The “Q” Element: The ship has a legitimate commercial reason to be there. It pays harbour fees, offloads legitimate cargo, and files a standard route plan. It hides its military function behind a wall of bureaucracy and commerce.

Royal Navy Use: This allows the UK to maintain a “listening watch” in sensitive areas where a Royal Navy warship would cause a diplomatic incident. It turns global logistics routes into a global intelligence network.

Specialised containers can even deploy antennas or drones to boost range, then retract them before entering port. It is global surveillance, hidden in plain sight.

The Soviets during the cold war often used Spy Trawlers and where crucial to them understanding western military capability. They provided the Soviets with the latest intel not just on on SIGINT and ELINT etc but also they gathered and collected other data like acoustic data of NATO submarines and movements.

The Drone Carrier: The Commercial Strike Deck

The era of the “Drone Carrier” is here, but it doesn’t necessarily require a flight deck the size of the Queen Elizabeth.

A merchant vessel offers a massive, stable platform for launching swarms of aerial drones (UAVs) or suicide surface vessels (USVs). Operators can conceal the launch mechanisms within the cargo hold or false containers. In a conflict, this “Commercial Carrier” can flood a combat zone with loitering munitions, overwhelming enemy air defences or swarming hostile shipping. It allows a navy to project air power without risking a multi-billion pound aircraft carrier.

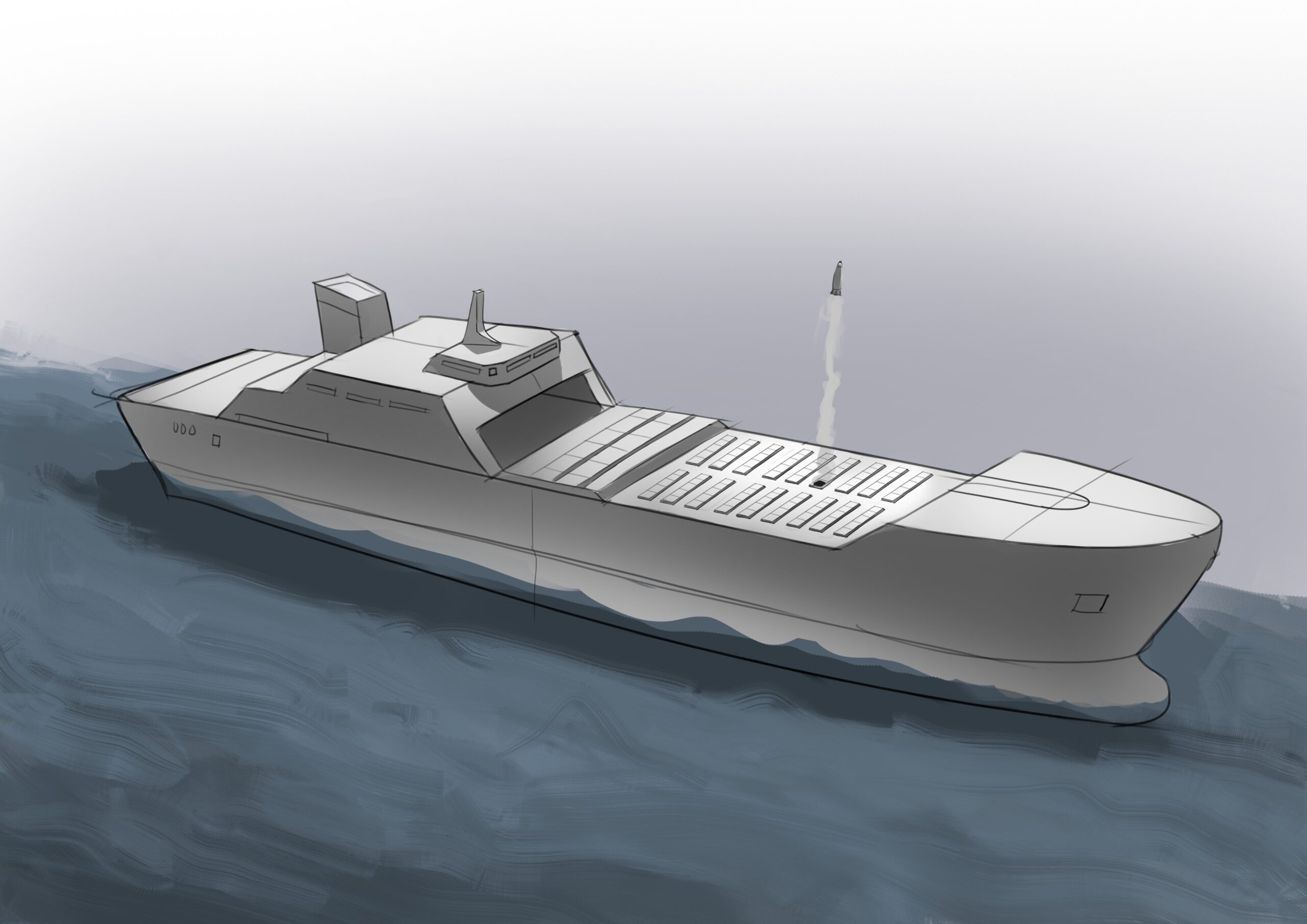

The “UXV Hive”: The Royal Navy’s New Mothership Concept

Perhaps the most tangible evolution of this concept is the “UXV Hive.” The Royal Navy faces a specific challenge: the “Gap.” It is retiring specialised minehunters, yet it cannot afford to tie up expensive Type 26 or Type 31 frigates for slow, tedious patrol tasks.

The Concept: The solution lies in the commercial offshore industry. The Navy is looking to vessels based on Offshore Support Vessel (OSV) or wind farm support hulls. These ships possess massive flat decks, huge internal volume for stores, and cranes designed for heavy lifting.

How it Works: Instead of oil rig equipment, the deck bristles with containerised drone launchers.

- Aerial: UAVs for wide-area surveillance.

- Surface/Subsurface: USVs and AUVs for mine hunting.

The “Q” Element: These ships operate effectively in the Grey Zone (like the Persian Gulf or North Sea). To the casual observer, they look like standard commercial contractors working on infrastructure. This appearance lowers the temperature of a standoff. However, if threatened, the “Mothership” can deploy a swarm of sensor or suicide drones to defend itself or sanitise a coastline.

Royal Navy Use Case: This approach allows the RN to clear mines or swarm a pirate skiff without risking a £1 billion warship. It moves the risk from the sailor to the drone, and from the frigate to a commercially derived hull.

Conclusion

The naval battles of the future may not start with a fleet of warships crossing the horizon. They might begin with a tugboat holding its ground, or a container opening on a harmless-looking freighter. The Q-ship has potential to return. Ukraine is making use of this in places like the Mediterranean to great success. Something like an up-armoured tug would have been useful during the Cod Wars where Iceland used fishing trawlers and rammed our more expensive and harder to replace warships.